By Alison Leckie | December 25, 2025

You are reviewing a term sheet or scrolling through a complex financial model for the first time. The rows are full of acronyms. You see CFADS, DSCR, SOFR. And then you hit one that appears in almost every deal: DSRA.

The Debt Service Reserve Account – DSRA for short – is one of the most common features in project finance loans. Yet it is also one of the more challenging and frequently misunderstood mechanics for junior analysts and other new modelers.

If you’ve ever wondered what a DSRA is and why lenders insist on having one, you are in the right place. In this post, we will break down the meaning, purpose, and mechanics of the Debt Service Reserve Account. We will also show you where it sits in the cash flow waterfall and how to model it effectively.

The Definition: What Is a DSRA?

At its simplest level, a DSRA is a savings account. It is a dedicated bank account that the borrower (the project company) must maintain to protect the lender.

The account usually holds enough cash to cover upcoming debt payments for a specific period. This is typically six months, but may vary from deal to deal.

If the project does not generate enough cash in a given period to pay the bank – perhaps due to underperformance, seasonality, increasing interest rates, or anything else – the project company can dip into this reserve account to help make the payment. This prevents a default.

Why Do Lenders Require It?

To understand the DSRA, you first have to understand the nature of project finance.

Energy and infrastructure deals are nearly always financed using non-recourse debt. This means the lenders will only be repaid from the cash flow of the project itself. They cannot ask the parent company or the shareholders of the project to pay back the loan if the project fails to produce enough cash flow.

That means that if a wind farm has a low wind period or a toll road sees less traffic than expected, the project might not have enough cash to pay the interest and principal due, which could result in a default.

With no natural safety net, lenders look to create one as a form of risk mitigation. Enter the DSRA. It acts as a buffer, giving the project breathing room.

Without a DSRA, the project would default immediately. With a DSRA, the project can use reserved cash to supplement project cash flow and pay the debt service. This buys time for the project to recover without triggering a crisis.

How It Works: The Three Stages of a DSRA

When we teach this concept in our financial modeling courses, we often break the lifecycle of a DSRA into three distinct stages.

- Initial Funding

The DSRA is usually funded before the project even starts operating. This happens no later than the day the project is placed into service, often known as the Commercial Operations Date (COD).

In that case, the money to fill the account comes from the construction budget and makes up a part of the total project costs. This means the equity investor effectively lends the money to the project to sit in this bank account.

- Usage (Drawing Down)

In a perfect world, that money will never be touched. It sits in the bank account for the entire life of the loan, after which it can be returned to the shareholders.

However, things do not always go to plan. If the cash flow available for debt service (CFADS) in a given period is lower than the debt service (principal and interest) due, the project faces a shortfall.

In this scenario, the lender allows the project to withdraw cash from the DSRA to fill the gap. This ensures the lenders get their full payment on time.

- Replenishment (Topping Up)

This is the part that often trips up modelers.

If funds from the DSRA are used to pay debt service, they must be paid back. The loan agreement will require the project company to refill the account as soon as possible.

In the next period, if the project has excess cash after paying its operating expenses and current debt service, that extra cash must go into the DSRA until it has been “topped up” to the required level. The project company cannot distribute dividends to shareholders until the DSRA is full again.

Calculating the Target Balance

How much money needs to be in the account?

The DSRA “Target Balance” is defined in the loan agreement. The most common standard is six months of future debt service. That may mean the next six months, or it could mean the maximum six months of debt service over the remaining amortization tenor of the loan.

At any point in time, the account must hold enough cash to pay the principal and interest due over the defined six month period.

For example:

- Imagine a solar project making quarterly debt service payments.

- The total principal + interest payment due on March 31, 2026, is $1,000,000.

- The total principal + interest payment due on June 30, 2026, is $1,000,000.

- As of December 31, 2025, the DSRA Target Balance would be the sum of these next two payments.

- Target Balance = $2,000,000.

As the loan gets paid off over time, the interest payments decrease. However, because debt service is typically sculpted based on expected future cash flow, interest decreasing does not necessarily mean that debt service decreases over time. Instead, debt service may go up and down along with forecast cash flows. Consequently, the DSRA Target Balance may increase or decrease over time, too. A decrease in the Target Balance releases cash back to the shareholders, while an increase would require further top-ups. Target Balance top-ups and releases will therefore impact cash available for distribution to equity over the life of the loan.

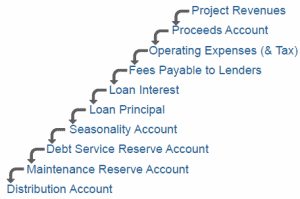

Where Does It Sit in the Cash Waterfall?

In project finance modeling, the “Cash Flow Waterfall” dictates the order of payments. It is like a series of overflowing buckets. The top bucket is filled first, and the spillover fills the next one.

The DSRA has a specific and critical place in this hierarchy.

Waterfalls vary from deal to deal, but a simplified view of the priority of payments may look like this:

- Operating Expenses: The project must pay to keep the lights on first.

- Debt Service: Next, the project needs to pay the bank interest and principal.

- DSRA Top-Up: If the reserve account is not full, cash goes here next. Releases may be made if possible.

- Major Maintenance Accounts: Reserves for future repairs.

- Shareholder Distributions: Equity investors get whatever is left at the bottom.

Notice that the DSRA Top-Up comes before distributions. This is a “lock-up” mechanism. If the reserve is not filled, the shareholders get zero dividends until it is fixed.

Cash vs. Letters of Credit (LC)

While we usually model the DSRA as a cash account, in the real world, investors hate leaving cash idle.

Cash sitting in a bank account earns very little interest. It drags down the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) for the equity investors because that money could be used elsewhere.

To solve this, many sophisticated sponsors replace the cash DSRA with a Letter of Credit (LC).

An LC is a guarantee from a bank. The bank promises to pay the lenders if the project cannot. In exchange, the project pays a fee to the bank. That fee becomes an operating expense.

This is a trade-off. The sponsor saves the upfront cash cost, but pays an ongoing fee instead. In our advanced courses, we help students model both scenarios to see which one yields better returns for a given project.

Modeling the DSRA in Excel

When building a financial model, the DSRA is often one of the trickier modules to build. Modelers often have to manage circular references because interest earned on the account may affect cash flow, income, and tax, which may in turn affect the cash flow again.

A robust DSRA module needs to track:

- The Opening Balance

- Target Balance calculations

- Funding (from construction or cash flow)

- Releases (when the target drops)

- Draws (to pay debt service)

- The Closing Balance

Building a model that can track and stress-test a DSRA is a core skill for any project finance analyst.

Summary

The DSRA is a lender’s insurance policy. It ensures that temporary cash flow issues do not turn into a default. For the project finance modeler, it represents a critical piece of the puzzle that sits between debt service and equity returns.

Understanding the “why” behind the DSRA makes the “how” much easier to model.

Pivotal180 Training

If you are ready to move beyond the definitions and start building these mechanics yourself, it might be time to check out a Pivotal180 course. We cover the DSRA in depth, along with every other component of a best-practice model, in our Renewable Energy Project Finance Modeling and Project Finance Modeling courses.

Explore all of our courses here. Come model with us!

Share This Resource

Related Blog Posts

Why do developers and engineers need to understand project finance models? Part 2

Anyone making project development, design and investment decisions must understand models to make smart choices and spend their time wisely. Our EPC contractor quit on us four days before financial close. It’s a story I tell often during our Renewable Energy Project Finance Modelling courses. And yes, it really did happen. Monday before a…

Why do developers and engineers need to understand project finance models?

Anyone making project development, design and investment decisions must understand models to make smart choices and spend their time wisely. ‘Matt – great news!’ our lead project developer yelled as he ran into our office. In the midst of a particularly challenging stretch, I needed some. Of late, it seemed like every project in our…