By Matt Davis | May 28, 2024

Tax Equity ‘Lite’: Same great taste, or just less filling?

Late last year, I took a look at the pros and cons of tax credit transferability – the new option created by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for non-tax efficient project sponsors to sell tax credits for cash rather than entering into tax equity partnerships. One of the key issues identified at that time was related to fair market value (FMV) step-ups for projects electing the ITC.

As I wrote:

In tax equity transactions, developer-sponsors typically sell the project to a partnership SPV. That sale can result in a “step-up” in the FMV of the project above its cost to build, often on the order of 20 to 30 percent. Since the value of the ITC is determined based on the value of the project, FMV step-ups create a proportional increase in ITC quantum.

Without the need for a tax equity partnership, sponsors taking the transferability route are unlikely to be able to effectuate an FMV step-up, reducing the potential ITC value a project can earn. The impact of this “lost” value will need to be considered when evaluating credit transfer options.

A potential solution mentioned to that problem was a Tax Equity ‘Lite’ (TE Lite) approach: the formation of a partnership not with a tax equity investor, but rather with another, likely also non-tax efficient party. The selling of the project into this new partnership recreates an opportunity for an FMV step-up.

So what is TE Lite – and is it really as good as the original, or just a blander, less filling version?

Why are you calling it Tax Equity ‘Lite’?

Aside from sounding better than ‘Diet Tax Equity’ (or TE Zero?), this new structure looks a lot like traditional tax equity partnerships, but a little, uh, ‘lite’-er. We still have a partnership with two parties, with pre-and post-flip periods, but this new co-investor (we’ll call them Sponsor 2) takes a lot less from the partnership than tax equity typically does, especially post-tax items.

Where tax equity investors usually receive 99% of the taxable income and tax credits from a project partnership, Sponsor 2 in a TE Lite deal will take much less – as little as one percent pre-flip – because, like the first sponsor, they generally aren’t an efficient taxpayer.

Like tax equity, Sponsor 2 will also get some cash from the project. Structures are still evolving, but most often, Sponsor 2 receives a coupon-like preferred cash distribution equal to some percentage of its initial investment each year. Sponsor 2 also typically gets some share of remaining project cash.

Using entirely made up numbers, if Sponsor 2 contributes 10% of the FMV of a project that costs $100 million to build and claims a 20% FMV step-up, they’ll invest $12 million. They might receive a pre-flip period preferred distribution of 12%, or a $1.44m annual preferred cash distribution in year 1. If they also receive 10% of project operating cash, and the project has annual EBITDA of $5 million, they’ll receive a further distribution of $356 thousand ($5m, less the $1.44m preferred payment, times 10%) in that year, for total cash distributions of just under $1.8m, or about 36% of total project cash before debt service. Post-flip, they might reduce to something like 5% of both income and cash, not unlike a common tax equity post-flip share.

36% — that’s a lot of cash! Even more than tax equity usually takes. Why are we doing this again?

TE Lite is not necessarily cheap! Again, this is a new structure and returns may vary greatly, but it’s probably safe to assume that most TE Lite-type investors are earning at least low double-digit returns on their money. That’s more expensive than most tax equity. And, critically, while tax equity earns most of their returns from tax losses and credits that tax-inefficient sponsors can’t use, TE Lite gets theirs from cash!

Given all that, large, highly-contracted projects that can attract tax equity dollars will likely be better off going that route. But many smaller, merchant revenue-heavy projects have trouble finding tax equity at all. While TE Lite can be expensive, it may still provide value for ITC projects value by enabling the FMV step-up.

Can this really work? Show me the math!

Let’s return to our simple, theoretical example of a project that costs $100 million to build (all ITC-eligible for simplicity). With no access to tax equity, that project might choose to sell its ITC. Unable to claim an FMV step-up, a 40% ITC (assuming a domestic content or energy community adder) might be sold for something like 92 cents on the dollar, or $36.8 million, received very soon after COD.

With a TE Lite structure, that same project might be able to claim an FMV step-up of, say, 20%. That would increase the value of the ITC it earns, sold at the same 92c, to $44.2m, or $43.7 million after giving 1% to Sponsor 2. That’s a net increase of $6.9 million in the sponsor’s pocket.

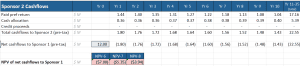

Assuming the same EBITDA and cash shares as described above, and a pre-flip period of 10 years, cash flows would look something like this (note that Sponsor 2’s preferred payment is assumed to reduce here as project cash allocations reduce their outstanding investment):

Depending on the first sponsor’s cost of capital (including cost of debt), the negative present value of the TE Lite investor’s share of cash may or may not exceed the additional value received from the FMV step-up!

Got it! It sounds like TE Lite might taste great after all!

It’s important to note that the example above is entirely illustrative. Actual structures, cash allocations and returns demanded by TE Lite investors may vary significantly from deal to deal and from investor to investor. Whether or not this structure adds value when compared to a direct ITC sale with no step-up will depend on a number of factors, including the TE Lite investor’s return, the sponsor’s cost of capital, and interactions with debt funding. Given that TE Lite investors will often invest on a percentage-of-FMV basis, this structure is likely to be more viable for projects that qualify for credit adders, increasing the overall value of the FMV step-up as it flows to ITC value.

Another key consideration is the size of the FMV step-up claimed. The appraisal and step-up process is one of the murkier areas of renewable energy finance. Tax equity investors have often shied away from accepting step-ups above 20% of construction costs, even if supported by a present value analysis. The types of projects that might need to consider a TE Lite approach, though, may often be merchant battery and/or solar or wind plus battery assets with significant uncontracted cash flow components that struggle to attract traditional TE. Those types of projects may be able to support more aggressive step-ups using an income approach, depending on merchant energy price and other revenue stream forecasts. But remember: tax advice should always be sought to confirm these items!

Want to learn more about TE Lite, project finance, and other new developments post-IRA? Check out the links below to learn more about Pivotal180 including all of our financial modeling courses and services. Come model with us!

- Short Courses – including our new program on post-IRA tax equity!

- Tax Equity and Hybrid Modeling

- Renewable Energy Project Finance Modeling

- Intro to Battery Storage & Financial Modeling

- Infrastructure Project Finance Modeling

- Financial Modeling Advisory & Consulting Services