By Haydn Palliser | September 10, 2020

Tax equity in US renewable energy transactions is one of the most bizarre and complicated structures in the project finance world. Add to that the overuse of acronyms (that I am sure are designed to complicate things further), just gaining a basic understanding can be almost impossible. No wonder people get lost in jargon.

One term that baffled me was PAYGO used in partnership flip structures. PAYGO is a common structure in wind transactions utilizing the Production Tax Credit (or ‘PTC’). This blog will ‘unbaffle’ PAYGO for you. That’s right, unbaffle. It’s my new word. If tax equity can make up words, why can’t I?

I have had the pleasure of co-authoring this blog with Pascal Schoneburg. Pascal is one of the most experienced tax equity modelers out there, so thanks to Pascal for helping demystify PAYGO! His bio is at the end of this blog.

Ok, it’s unbaffle time.

Tax equity 101: the benefits recap

We assume you know the basic structure of tax equity transactions. If not, we recommend (of course) the Pivotal180 tax equity financial modeling course.

Despite our presumption of your prior knowledge, we should touch on the concepts within tax equity most relevant to PAYGO.

#1 – Disproportionate allocations

Allocations of tax benefits and cash benefits can be disproportionately allocated to the investor (tax equity) and the sponsor (equity), AND they can change over time. Below is a common structure for a wind transaction. PAYGO is used with the Production Tax Credit (PTC), which is adopted for wind transactions and NOT with the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) which is used predominantly with solar transactions.

The diagram below shows how the tax equity investor will take 99% of the tax benefits (tax losses and PTC) for 10 years (period 1), after which they step down to taking 5% of the same in period 2. The tax equity investor in our example is taking 20% of cash in period 1, followed by 5% in period 2. The change in allocations between period 1 and period 2 is called ‘the flip’.

#2 Benefits to tax equity investor

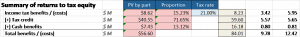

To explain the broad quantum of tax and cash benefits, we will use the below set of ‘cashflows’ to the tax equity investor. Whilst these are close to reality, just like ‘unbaffle’ is a made-up word, the values are made up.

The PTC tax credit is so incredibly important from a returns perspective, being ~70% of the returns to the tax equity investor.

Cash and income tax benefits split the remainder of their return on a present value basis. Tax is a BENEFIT to the tax equity investor as they can use the partnership’s taxable losses predominately in the first ~6 years (due to accelerated depreciation) to offset other positive income in their business. After ~year 6, the partnership will typically start to owe taxes on the project.

A note on benefits

We are often asked what matters most to a tax equity investor. Assuming a 21% federal tax rate (and no state taxes):

- A tax credit is a $ for $ reduction of taxes. A $1 tax credit is worth $1 to a tax equity investor.

- Cash is ultimately taxed, so cash is worth cash amount x (1-tax rate). $1 of cash is worth $79c to the tax equity investor (assuming no state tax).

- Tax losses reduce taxable income. $1 of tax losses is worth 21c to a tax equity investor.

#3 Flip period

As seen above, the PTC is the largest component of returns to the tax equity investor. The PTC is a tax credit for 10 years. From year 11, the project will most likely have taxes due and no further PTC.

The tax equity investor is investing primarily for the tax benefits, thus it makes sense that they wish to step down their allocations after year 10 (and in most cases due to merchant banking rules must actually liquidate / sell off their investment).

Sizing tax equity’s investment

Tax equity investors discount their future expected cash flows until the flip date (i.e. the end of year 10) at their hurdle rate (called the ‘target yield’). The result is the present value, which is the maximum amount they would be willing to invest in the project.

In our example from above (shown again below), the investor would be willing to invest up to $56.6m. Tax equity’s investment is typically around 50-65% of the total funding of a wind project.

Warning on cash flow forecasts

One thing to be aware of is that the assumptions underpinning generation and cash flow used to size tax equity may be different to the sponsor’s assumptions. For example, the P50 net capacity factor that the tax equity investor uses to size their investment may be lower than that of the sponsor, along with adjustments to basis assumptions, merchant forecast curves, operating expenses etc. Which case to use as the “funding model” (the model used to size the investment), Sponsor P50 vs. tax equity P50 is a negotiation point between the two parties.

There are a many other considerations for tax equity in terms of sizing. The items most relevant to PAYGO, is that tax equity will check their returns, cash flows, and flip date under several ‘P’ scenarios, including P75, P90, P95 and P99. Tax equity is typically conservative, so they will run many scenarios and look at the P99 as a threshold for their “worst case scenario” and use this as a basis to drive structuring terms. This is a more conservative case for tax equity. They can analyze a P99 generation case to see if they get an appropriate return (or get their money back) in a downside case as well as how far said downside pushes out their expected flip term.

Risk to tax equity’s investment

Tax equity investors have ‘equity’ within their name. But tax equity investors don’t make management decisions and their prime focus is to protect their downside. The investment is much more debt-like than equity.

So with that in mind, what’s the potential downside to a tax equity investor?

- The generation is lower than expected

- That cash flows are lower than expected (a result of generation, or perhaps costs being higher)

- Tax losses being of lower value

Tax losses being of lower value (i.e. less tax losses) is normally a sign that the project is performing well. Assuming appropriate depreciation categories have been applied, lower tax losses is likely due to higher EBITDA, indicating cash flow is higher than expected (and possibly tax credits). So this isn’t the big risk.

The PTC is the largest part of tax equity’s returns, so this is the item they rightly worry about the most. PTC is earned on the actual energy generated and sold by the project, so if there is an issue with production they earn less.

Enter PAYGO to mitigate the risk of lower energy production

The concept

Without PAYGO, the tax equity investor would invest 100% of their committed funding during the construction period (or at the Commercial Operations Date) just like equity investors and lenders do.

The tax equity investor’s biggest worry is that generation could be lower than the P50 forecast they sized their investment on. With less generation, the PTC would reduce.

There is a way in which the tax equity investor can contribute a portion of their investment during construction and the remainder in each of the 10 years when PTC is earned IF the expected P50 production is met.

Here’s the logic from the perspective of the tax equity investor:

- Rather than commit 100% of their funding prior to financial close or at the Commercial Operations Date (“COD”)

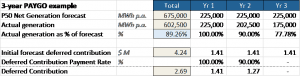

- Tax equity investor will commit to contribute 75% of their investment by COD with the remaining 25% contingent on actual production over 10 years (called a ‘Deferred Capital Contribution’) based on a sliding scale of the Base Payment Rate (defined below).

- Note: at least 75% of the investment must be fixed and determinable obligations NOT contingent either in amount or certainty under the tax code. This is the reason for deferred contributions being no greater than 25%.

- If the project hits the expected P50 generation (either annually or semi-annually over the trailing 6/12 months), the tax equity investor contributes their agreed deferred contribution

- If generation is less than the forecast P50 generation utilized in the funding model, they scale back their deferred contributions accordingly. This is effectively a hedge, by reducing payments if the P50 generation is less than (over a trailing 6/12 month period) than what was forecasted in the funding model.

The impact of not meeting the P50 forecast

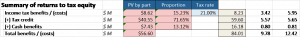

The table below provides an example of how the deferred capital contribution is scaled back if the agreed P50 forecast is not met. The Base Payment Rate is the expected payment to be received if the project generates what was expected under the initial P50 forecast.

If actual generation in a given period is 90% of the expected P50 production level initially forecast, the tax equity investor will only contribute 90% of the deferred contributions.

If generation is less than 80% of the agreed P50 production level in any given period, the tax equity investor will not invest their deferred contribution.

What may not be obvious here, is that P99 is often around ~80% of the P50 generation (depending on the standard deviation). Less than 80% of the production level may refer to a P99 case. The P99 case may therefore result in tax equity not investing ANY of the deferred contributions.

A PAYGO example

Mechanics

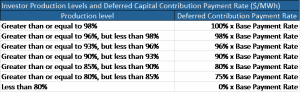

The deferred contribution in our 3-year example (in each year) is:

Year 1: The actual generation = the forecast generation. The full deferred payment is made.

Year 2: Actual generation is 90% of the forecast generation. Based on table 1, 90% of the deferred contribution is made.

Year 3: Actual generation is 78% of the forecast generation. Based on table 1, the deferred payment is not made.

Economics

First of all, Tax Equity is putting a portion of their capital contributions into the project later with PAYGO than without a PAYGO structure. This can provide the Tax Equity investor a similar if not equal return, with substantially less risk. What’s not to love……..for the tax equity investor.

Secondly, if the P99 generation case were 80% of P50 in every period, tax equity would only contribute 75% of their expected total investment (i.e. they will not invest any Deferred Capital Contributions). This means tax equity is contributing 75% of the value for 80% of the benefits. If you run a P99 case in your model, you may see that, although the flip date could be delayed, tax equity does not lose any value in the P99 case compared to the P50 case. Sound like equity to you….?

Note on PAYGO with 45Q tax credit

45Q is a tax credit relating to the capture of C02. Whilst we won’t go into 45Q here, it is a tax credit that is earned over 12 years as C02 is captured.

As such it may also be a suitable tax credit for a PAYGO structure. The main difference we are aware of is that the 45Q credit requires only 50% of the investment from tax equity to be fixed and determinable obligations NOT contingent either in amount or certainty. This means tax equity could have the remaining 50% contingent on actual C02 capture (i.e. only invest 50% before COD).

Implications on PAYGO for the sponsor

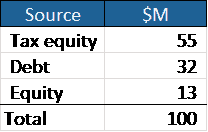

Let’s assume the project cost is $100m. Tax equity is sized based on the present value of their benefits, as is debt. Equity must fund the remainder of the funding needs. Here is an example capital stack without PAYGO:

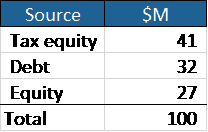

If Tax Equity only contributes 75% of their investment within the construction period under a PAYGO structure, equity needs to fund 25% of tax equity’s commitment during the construction period.

Not only does equity have to fund more money upfront, even if P50 is met, equity funds more today in return for cash from the tax equity investor in the future. This has a time value of money impact to equity, lowering their returns.

So why would the Sponsor agree to PAYGO???

Much of this relates to the market. Tax Equity is complicated such that there are limited investors in the market. Demand is therefore greater than supply. Smaller un-rated sponsors have very limited negotiating power, although larger entities have more room to negotiate terms.

Finally, there are some additional options that can help the sponsor fund the 25% of unfunded tax equity commitments. If you would like to discuss this, please reach out!

Beware sponsors

Worst case in a PAYGO deal for you is that you are overly aggressive on wind forecasts. If the forecast is not met, you will fund an additional portion of capital for which you get no return. This structure therefore puts a little more pressure on sponsors to be a little more conservative. This on its own, is a good outcome from PAYGO and is one reason lenders can like the structure.

Maybe lenders should call themselves, ‘fixed return equity’ and try a similar structure….

Share This Resource